No surprise, holidays constitute a challenge after significant loss, and not just the big ones, either. I mean, sure, Christmas, Thanksgiving, Easter–all associated with family, fun, gratitude. Birthdays and anniversaries, naturally you feel the absence of your loved one. Those are the times when you expect discomfort, and others are poised to offer support.

But I’ve been surprised, even ambushed, by the “lesser” holidays, like this recent Fourth of July. I have years of memories of watching fireworks with our kids, and later just the two of us. Lee always had a camera on hand to capture the explosions of light in the night sky. About 14 or 15 years ago, we drove to the Twin Cities for the holiday weekend, and the whole family went to White Bear Lake to watch the fireworks display over the lake. No idea I’d call that community “home” one day, but here I am.

Over the five years of Lee’s illness, I don’t think a single holiday was left untouched. One Fourth that stands out was July 2016, when our entire family met up in Estes Park, CO. With both kids living far away, wrangling all of us to one place was rare, and we were eager to enjoy time with our kids and grandson. The repeated bouts of nausea had mostly abated at that point, but sure enough, it hit hard as soon as we arrived in the mountains. Lee tried to soldier through, but after losing his breakfast in a parking lot, spent a couple days in bed at our hotel. I stayed back with him, afraid he’d need a trip to the ER for rehydration (he didn’t, thank goodness), and we missed out on the fun. He did recover enough to enjoy a final family afternoon and evening on the 4th, but went back to bed early, and I recall standing outside our hotel, watching fireworks over Lake Estes by myself. A few weeks later, we had our first appointment at Mayo Clinic, and the horrid diagnosis two months after that.

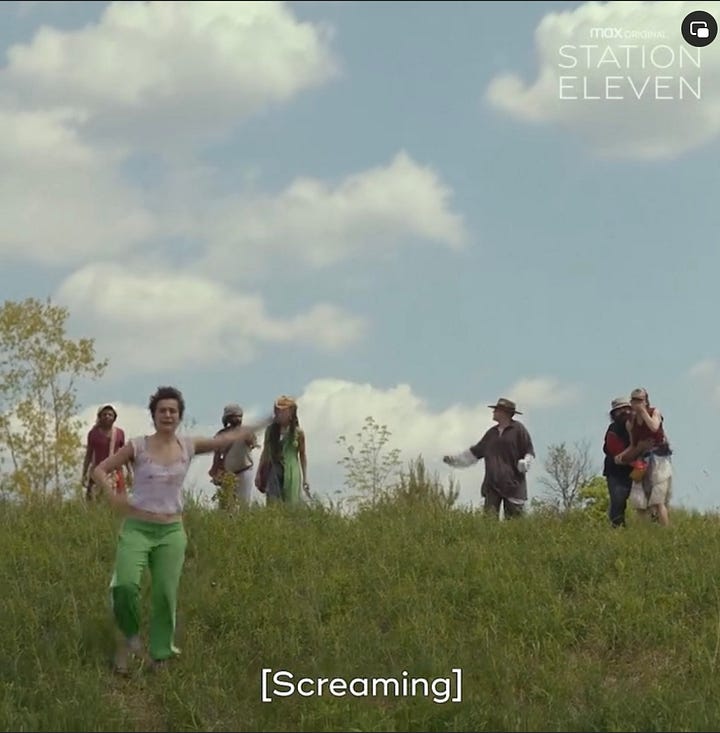

A couple years ago, I watched “Station Eleven,” a TV series set in a post-pandemic apocalypse (just for a change of pace from the daily news). In one scene, the core group of ragtag characters traveled on foot to join others at a safe compound. Finally in sight of their goal, they had only to cross a flowery meadow, and started to sprint across, but were stopped cold by warning shots and shouts from the compound, saying they were in a minefield.

The condition of my heart is much like that beautiful minefield. On the surface, it looks good, even thriving and blooming. But underneath, it’s pitted with landmines, and it doesn’t take much to trigger one. A stray step, an evocative memory, a difficult interaction, a dumb platitude, a second-tier holiday, and kablooey, it all goes up in dust.

Over time, I’ve mapped out just where some of the mines lurk, and can avoid them, but not always. I spend a lot of energy picking my way across that field, sometimes shying away from unexplored areas just in case they hold danger, likely cheating myself of something good in the process.

On the TV show, one panicky character charged across the minefield, despite the warnings, and made it to the compound, thereby marking a safe path that the others followed. But that’s TV. I’m the only character navigating my heart’s particular minefield, and while I can look to others for advice on how they crossed their own minefields, mine is unique to me. I’m the only one here. And it’s up to me to stay frozen in fear or dare to take a step.

How do you get rid of landmines? You call in the bomb squad to blow them up. Unlike actual landmines, mine seem rigged to explode repeatedly, but they eventually lose some of their destructive power. Therapy, journaling, my grief writing course are all part of the disarming process, wringing the difficult emotions out of them through iteration. It’s difficult work, easy to avoid with more pleasant distractions (like post-apocalyptic TV shows!), but effective in the long run.

I’m learning to catch myself before I go down an emotional path lined with landmines, reminding myself to stick to the safe way I’ve mapped out through hard won experience. As an example, a specific old resentment cropped up AGAIN in my musings recently, and I’m so sick of revisiting it that I’ve started saying, “I’m not having this argument with you anymore” in my head when I catch myself. It usually works.

I also try to remember that I want to come out of this rest-of-my-life process a kinder, more compassionate person. Those venturing into my minefield are often just plainly ignorant of so much—no idea where they’re standing (looks like a meadow to them!), no personal experience of living in such a place. I used to be one of them, saying the stupid things I assumed were comforting to the bereaved.

I’m the one whose eyes have been opened, and I see two things I can do in this situation. The first thing is putting on some protective gear, like a bomb squad would wear. Again, I think this comes from reading about grief, tapping into the resources at my disposal, opening my eyes to the support that is available, putting on my “this is normal!” padding.

The other thing I can do is gently push back when others say uninformed things that hurt, or offer “support” that is anything but. I can give them a glimpse of where I’m standing and what they’ve stumbled into, educate them just a bit. That’s my purpose in writing and publishing here on Substack. It’s not easy; in fact, it’s nearly impossible to do in person, and so much simpler to just nod and go along with whatever was offered, and then shy away from confiding in that person again. But if I don’t, it’s likely to create even more landmines to pick my way around, and I lose trust in those offering what they consider support. Most people truly do want to do or say the thing that actually comforts and helps.

It’s not fair that grievers are handed this additional responsibility to clue others in just when we’re at our lowest point, but it is a way of redeeming the whole grief business a bit, bringing some good out of it, reducing the number of landmines out there just waiting to be tripped. Maybe.

Yes to it all, Joyce. Eloquent and clear description of the grief transformation. I find greeting card sections of stores are a mine field for me. The mine field metaphor fits so well.